Kuaapy

Ayvu [Revista

Científico-Pedagógica], vol. 15 (núm. 15), pp. 107-141. INAES

Publicaciones.

eISSN 3078-4913. ISSN-L 224-7408. Licencia CC BY NC

SA 4.0

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Recibido el 29/2/2024 / Aceptado el 25/5/2024

Artículos

Analysing the classroom

environment: instrument creation, validation, and implementation

Análisis del entorno del aula: creación, validación y aplicación de instrumentos

Analisando o ambiente da sala de aula: criação,

validação e implementação de instrumentos

Marta Rovira-Mañé

Universitat Internacional de Catalunya: Barcelona, España

marta.rovira@uic.es

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4755-5333

Jaume Camps Bansell

Universitat Internacional de Catalunya: Barcelona, España

jaumecamps@uic.cat

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0930-1136

Abstract

This scientific paper

focuses on the creation of a new instrument to respond to the need to analyze

the quality of the classroom environment of today's classrooms, and

consequently, to be able to correct what is needed. Previous projects had some

shortcomings due to the year they were published, such as the emergence of new

technologies in the classroom, consequently a review and update seemed

necessary. Therefore, a new instrument has been created that adapts to the

current needs of students in the middle and upper cycle of primary school (8-12

years). All these characteristics that affect students have been assessed in

five variables: interest and motivation, satisfaction, relationship between

teacher and student, relationship among students and communication. After being

validated, the tool has been implemented in 46 classrooms of schools with

different characteristics and context. The results obtained have been analyzed

and statistically validated by IBM SPSS program through Cronbach's alpha, which

has ensured that there is consistency in each of the answers.

Keywords

Pedagogy; school; healthcare; learning environment;

school climate

Resumen

Este artículo científico se centra en la creación de un nuevo

instrumento para dar respuesta a la necesidad de analizar la calidad del

ambiente de las aulas actuales, y en consecuencia poder corregir lo oportuno.

Los proyectos existentes analizados presentan algunas carencias debido a su

antigüedad, por lo que nos pareció necesaria una revisión y actualización. Para

ello hemos creado un instrumento, que se adapta a las necesidades actuales de

los alumnos de ciclo medio y superior de primaria (8-12 años). Las influencias

del entorno que afectan a los estudiantes han sido clasificadas y evaluadas a

partir de cinco variables: interés y motivación, satisfacción, relación entre

profesor y alumno, relación entre alumnos y comunicación. La herramienta ha

sido implementada en 46 clases de escuelas con diferentes características y

contextos. Los resultados obtenidos han sido analizados y validados

estadísticamente con el programa IBM SPSS a través del alfa de Cronbach, lo que

ha asegurado que haya consistencia en cada una de las respuestas.

Palabras clave

Pedagogía;

escuela; cuidado de la salud; entornos de aprendizaje; clima escolar

Resumo

Este artigo científico

se concentra na criação de um novo instrumento para analisar a qualidade do

ambiente atual da sala de aula e poder corrigir quando necessário. Os projetos

existentes que analisamos têm algumas deficiências devido à sua antiguidade,

por isso consideramos necessário revisá-los e atualizá-los. Para isso, criamos

um instrumento adaptado às necessidades atuais dos alunos do ensino fundamental

II e superior (8 a 12 anos). As influências do ambiente que afetam os

estudantes foram classificadas e avaliadas com base em cinco variáveis:

interesse e motivação, satisfação, relação professor-aluno, relação entre

alunos e comunicação. A ferramenta foi aplicada em 46 salas de aula de escolas

com diferentes características e contextos. Os resultados foram analisados e

validados estatisticamente utilizando o programa IBM SPSS, por meio do alfa de Cronbach, garantindo a consistência das respostas.

Palavras-chave

Pedagogia; escola; saúde; ambiente de

aprendizagem; clima escolar

Introduction

The world is changing, and schools should keep pace

because they are educating the future members of society. Therefore, it is

essential to provide them with the skills they need to integrate into a society

that is new to them and constantly changing.

In addition, new technologies play an important role

in this process of change, because unlike years ago, students have access to

all the concepts they have learned in subjects such as history, languages,

natural sciences… with just one click. For this reason, some schools focus not

only on teaching content suggested by the curriculum, but also on training

people who are open-minded, self-confident, respectful, sustainable,

cooperative, freethinking, among others.

However, very few of them care about analysing the context in the classroom. Are students

satisfied with their lessons? Is there disrespect among peers? Are students

afraid to intervene in class to express their opinions or ask questions? Do

students trust the teacher to express how they feel? Is the social environment

of the classroom promoting the learning process?

All these questions are difficult to assess through an

observational method, as not all the situations are visible to everyone and

there are things that slip from our grasp. For this reason, teachers and

schools should be provided with a tool that gives students a voice, so that

educators can get feedback on the quality of the environment, correct what is

necessary and create spaces conductive to learning and safety.

In 1970, there were many experts who became interested

in the topic of the social climate in the classroom and formulated a definition

(Brandt & Weinert, 1981). It has been found that the classroom environment

is one of the school variables that best predicts learning (Maldonado, 2016;

UNESCO, 2014).

By 2009, experts such as Pérez, Ramos and López (2009)

and González, Touron and Tejedor (2012) created and

validated the instrument due to an increasing demand from teachers. However,

due to the publication year of the study, it does not consider the current

characteristics that surround second and third cycle students in the classroom.

In addition, it is not accessible to all teachers because of the difficulty in

interpreting the results.

It is difficult to define the classroom environment,

because it is a concept that encompasses many dimensions grouped into two main

levels: the material part, including infrastructure and furniture; and the

immaterial which includes people and the interactions between them in the

classroom atmosphere (Arón & Milicic, 2004).

Therefore, the most accurate definition is «the perception that each member of

the classroom has about their internal and daily life. This perception promotes

individual and collective behaviour (a way of

relating to each other and with the teacher, a way of being ...) that at the

same time influences the environment itself» (Pérez, Ramos & López, 2009,

p.223). As can be seen in the definition, the student, the teacher, and the

curriculum are the three of the elements that make up the classroom atmosphere

and the balance between them positively affects the environment as well as the

teaching and learning process (Vaello, 2011). It

should be noted that within these three major groups, several factors

surrounding the students in the classroom environment must be considered. For

example, interest and motivation, relationships between students and them with

the teacher, communication, physical space, among others. (Barreda, 2012;

Moreno et al., 2011; Villanueva, 2016; Rojas, 2013)

Firstly, it is important to consider that there is a

low level of motivation among students, which has a negative impact on social

satisfaction, interpersonal relationships, social coexistence among others

(Manzano y Valero-Valenzuela, 2019). According to Manzano-Sánchez (2021), this

demotivation begins in the last years of primary school, increasing the

possibility of school failure and continues in secondary school. For this

reason, Manzano-Sanchez (2021) says that interventions are needed to improve motivation

and thus strengthen a good classroom atmosphere.

Secondly, when creating a good environment, the

teacher must also be motivated and interested in the students. In this way,

they will not only show certain competencies, skills, and mastery of the

content, but will also implement a motivating and varied methodology, a

pleasant distribution of space and establish a respectful interaction by having

a “pedagogical touch” (Baños et al., 2017; Biggs,

2005; Perrenoud, 2005; Arón y Milicic, 1999).

Artavia, (2005), defines the concept of pedagogical touch as the ability to

know how to interpret thoughts, feelings, and inner desires through facial

expression and body language. For this reason, the relationship between teacher

and student may be affected by the methodology applied, the distribution of

space, among others (Barreda, 2012).

Following this line, it should be noted that there are

some teaching styles that positively or negatively affect the existent

relationships in the classroom (González, Conde, Díaz, García, & Ricoy,

2018). An authoritarian teacher is the one who pressures all students to do

their homework following their perfectly established model, even if it is not

the most suitable for their level. If the student decides to do the task using

the established method, the teacher is pleasant, on the contrary, the professor

shows a bad mood since the student does not obey (Marchesi & Hernández,

2000, as cited in Figueroa, 2012). In this way, a distance is created between

the teacher and the student, making students afraid to ask questions or

communicate social or emotional problems to the teacher. Therefore, according

to Goleman (1999), the authoritarian leadership style has a negative impact on

the classroom environment.

On the other hand, there is the democratic style,

which “encourages group members to determine their goals and make decisions,

striving for everyone to participate. Responsibility is shared with all members

of the group” (Cuadrado Reyes, 2009, p.3).

In addition, the teacher is empathetic, both inside

and outside the classroom, caring about emotional and social issues; allows

students to express their concerns and doubts that may arise; adapts the

methodologies to the individual needs of each student and with the aim of

achieving the common good, establishes equal rules for the whole class

(Madrigal, 2004). In this way, a relationship of trust and empathy is

developed, and as a result, according to Goleman (1999), the democratic

leadership style has a positive impact on the classroom environment.

Following the idea mentioned above, the teaching style

not only affects the relationship between teacher and student, but also the

student’s participation, level of attention and understanding of the lesson. If

there is a relationship of trust and empathy between teacher and student,

communication between the two will be more positive, open, and constructive

(Vieira, 2007). Although communication style may be affected by gender,

culture, and other individual characteristics (Camargo Uribe & Hederich Martínez, 2007).

In addition, it is very important to consider the

interaction between teachers, because during the internships in the schools it

was observed that communication between teachers positively affects the

students and therefore the atmosphere of the classroom. For example, teachers

from a school in the Vallès Occidental

region, meet every week to distribute the weekly homework in a more equitable

way. This has had a positive effect as students have time to complete their

homework without any anxiety due to the amount of work that has

to be done outside school.

Finally, it is important to establish good

communication between the school and the family, because if there is no good

communication, the family context can become a problem and consequently have a

negative effect on students (Estévez et al., 2005). Parental involvement in

school is very important, having a positive effect on students and on parents

who are more satisfied with the teachers and the school. In addition, teachers

are more involved in activities, have more competence in their profession and

have more empathy with students and families. As a result, the student has a

positive attitude towards authority and a positive perception of the school,

which promotes integration and improves academic performance. (Moreno et al.,

2009).

In the last century, the classroom was already

considered an artificial space where students are placed next to each other

without prior ties, day after day, with structures of communication and

authority (Quintana, 1980). This grouping of students

without a free decision to join makes it a handicap because it can negatively

affect the emotional perception of relationships between students (Biscarri, 2000).

This is one of the reasons why problematic situations,

misunderstandings and disputes arise in the classroom, which can be visible to

the eyes of the teachers so they generally act as mediators (Munne, 2015), or

hidden from them, which may develop into school bullying. Bullying is not a new

problem but has been present in schools since the 19th century and has been

evolving to the present day. (López & Sabater, 2019). The victim suffers

physical and psychological aggression, exclusion, their material is not

respected among others. As a result, there are symptoms of stress, depression,

and nervousness to participate in class leading to school failure. (Oñate &

Piñuel, 2007)

As can be seen, the relationship between students is

an issue that directly affects the classroom environment and therefore all the

aspects mentioned above must be considered to evaluate it. Some factors that

influence student satisfaction in the classroom, such as new technologies,

class distribution, order and noise during theoretical explanations, and

teacher competence.

On the one hand, according to Gámiz

(2009), Dugarte y Guanipa (2009) y Marqués (2010)

the digital world demands changes in education and teachers are responsible for

applying information and communication technologies in their educational action

to achieve a more student-centered and personalized paradigm. Information and

communication technologies bring many advantages and improve the quality of

teaching (Almenara, 2007), but they are not yet widely used in class due to the

low training of primary school teachers (Martín, 2009).

On the other hand, the distribution, order, noise, and

equipment of the physical classroom also have a positive or negative effect on

the students who make it up (Gairín, 1995). For

example, it is essential to allocate a space in the classroom to display the

work done by students in the classroom, as it encourages and motivates them and

at the same time makes the class a more personal and warm space which

positively affects the classroom environment (Cela & Palou, 1997).

The general objectives

of the paper are:

A. Create and validate a new instrument to assess the

classroom environment, so that it adapts to the new characteristics that

surround the students from the second and third cycle in the current

classrooms.

B. Analyse samples from different classrooms to present in a practical way how the

instrument works.

C. Validate and verify the effectiveness of the

instrument in schools with different contexts, such as private, semi-private,

public, urban, and rural schools in Catalonia and one in Helsinki, Finland.

Methods

Creation of the instrument

The instrument was created by the researcher of this

paper but was mainly inspired by the journal article of Perez, Ramos &

Lopez (2009), which is a previous tool that assesses the classroom environment.

However, this tool developed in 2009 has some shortcomings due to the year it

was published, such as the emergence of new technologies in the classroom.

Therefore, the instrument created in this paper considers three other articles.

The first one is a journal article by González, Touron and Tejedor (2012) from which some ideas of

questions related to the physical classroom were extracted. Second, this tool

was also inspired by the journal article from Vásquez, Zuluaga and Fernández

(2012) in which there is a tool to detect bullying and cyberbullying. Finally,

to assess the impact of technologies on the classroom environment, the article

by Mousavi, Mohammadi, Mojtahedzadeh, Shirazi and

Rashidi (2020) was considered.

After analysing the above

articles, two questionnaires of 37 questions each were created as a final

product, one for the middle cycle (8-10 years old) and the other for the upper

cycle (10-12 years old) (Appendix 1).

These two questionnaires differ only in question

number 36, which in the upper cycle deals with cyberbullying, while in the

middle cycle it focuses on bullying. It was decided to change this question in

the middle cycle, since in the interview prior to the administration of the

questionnaire, some teachers commented that middle school students do not

communicate via the Internet because they do not have a cell phone or other

devices.

The questionnaire was designed to measure the

following variables: interest and motivation, satisfaction, teacher-student

relationship, peers’ relationship, and communication; considering new

technologies, student fear, bullying, among others, all the characteristics

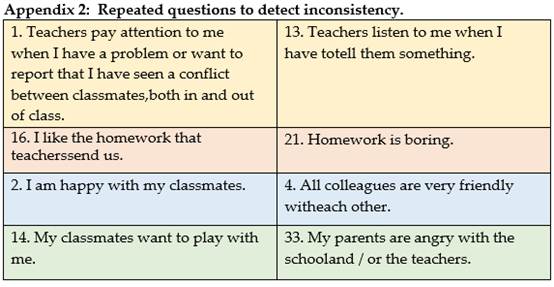

that currently surround students and affect the atmosphere (Appendix 2).

It should be noted that some accommodation has been

made to help all students with different learning diversities, disorders, and

languages, and consequently ensuring that everyone understands what is being

asked. For example, the audio of the questionnaire (Rovira-Mañé,

2022) was made to facilitate comprehension, and it was printed in large size to

accommodate students with dyslexia and other disorders. Moreover, the survey

was translated into Catalan, English, Finnish, Russian, Korean, among others, in order to attend to all those newcomer students who do not

yet speak the official language of the school. Finally, teachers were able to

choose whether to complete the questionnaire online through the Google Forms

application or with printed paper depending on the general characteristics and

needs of the students in the class.

Validation of the instrument

To create a rigorous instrument, first before

implementing the questionnaire a qualitative validation of the questions was

done, asking for the opinion of different experts.

Secondly, after the application of the questionnaires

in different classrooms, a statistical validation of the results obtained was

made, both answers obtained in the whole class by means of the variables

Cronbach’s alpha statistics, and individually through repeated questions

formulated differently.

After the validations, if the answers were consistent,

the final report of the environment of each classroom

was elaborated, taking into account the 5 dimensions analysed. The validations carried out are explained in

detail below.

On the one hand, before the implementation of the

questionnaire in the classroom, the questions of this tool were validated by

education professionals and by members of the Fundació

de Moviments de Renovació Pedagògica de Catalunya (FMRPC), which is a Catalan entity

created in 1981 with the aim of having a quality Catalan public school. It

should be noted that appropriate corrections were made based on this expert

validation (Appendix 2). These experts have considered the validity of the

content where it is verified that the questions include all aspects of the

different variables studied and the validity of construct to know if the

questions represent all the characteristics that affect the classroom

environment. In addition, they also analysed the

criterion validity, that is, whether the questions of each variable are

related and meaningful.

On the other hand, after the implementation the

answers obtained in each of the classes were validated from a statistical point

of view through the IBM SPSS program.

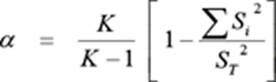

Firstly, the value of the Cronbach’s alpha is checked,

which indicates the consistency and homogeneity of the data, so it is necessary

to validate the answers before making any interpretation. To calculate it, the

program uses the following formula, where Si² is the variance of the answers to

a question, St² is the variance of the total values observed, and k is the

number of questions.

Figure 1

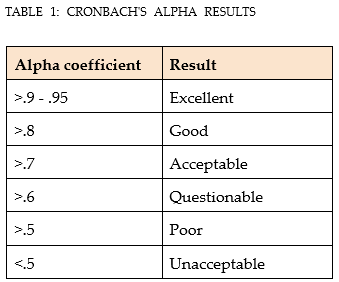

According to a group of workers from the American

Psychological Association (Wilkinson & APA Task Force on Statistical

Inference, 1999), Cronbach's alpha is the most widely used coefficient in the

social sciences and health articles. This idea is supported by a study stating

that 75% of publications are based on Cronbach’s alpha. (Hogan et al., as cited

in Frías, 2021)

Therefore, to evaluate and represent the reliability

of the answers, Cronbach's alpha gives a value from 0 to 1 for each question in

the tool, where the closer to 1 the greater the consistency of the responses analysed within a class. In other words, if the answers

provided by students of the same class were identical, they would be perfectly

correlated and therefore the result would be equal to 1. Otherwise, if there is

no relationship among the answers of the participants the value of alpha would

be equal to 0. To determine the consistency of the data, George and Mallery

(2003, p.231) recommend using the following table to evaluate the results

according to Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

For this reason, in this project, it was determined

that the Cronbach's alpha variable must be above 70% (> = 0.7) to be

considered a reliable questionnaire.

If the analysis of the answers shows a result of the

Cronbach’s variable below 60%, the evaluation is done by eliminating any of the

questions that may have affected the lack of coherence, which could be a

misunderstanding of the question. At this point, this answer would be removed,

and the analysis would be continued, but if after deleting any of the

questions, we still have the variable result below 60%, then it would be

unreasonable to continue the study of that class.

In addition, extra control was added in this study,

foreign to Cronbach's alpha. It consists in adding to the questionnaire

repeated questions but formulated differently (Appendix 3), to be able to

detect and exclude any student who has answered the questions randomly and that

therefore has contradictory answers. To detect them, the correlation value was

checked between those repeated questions, if it comes out above, 700 individual

questionnaires will be analysed to see if there are

any students who have contradicted in more than one repeated question. If so,

the answers from that survey are removed and the class information will be

re-processed in the program. Conversely, if it is observed that a student only

contradicts one of the repeated questions, the questionnaire will be considered

because it may have been a misunderstanding. The correlation means similarity,

so if you get 1 it means that the results of the two questions are the same,

while with a 0 they don't look alike. In summary, this study also tries to

contrast and ensure that there are no contradictions between the answers of the same individual questionnaire. In this way,

inconsistencies can be detected, and the participant can be excluded.

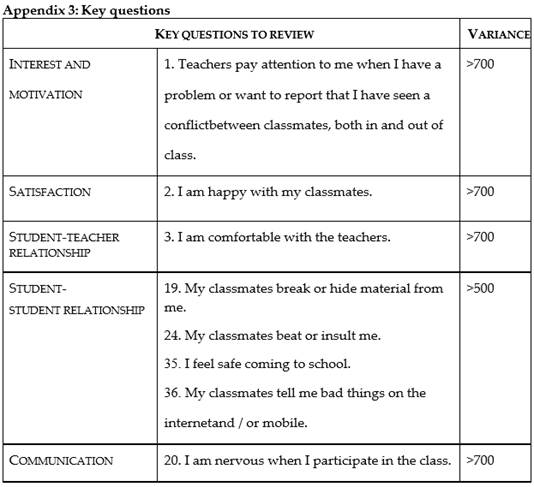

Once it has been ensured that all the data entered in

the program for each questionnaire is valid, the information is analysed in detail in a global way considering the variance

of the different questions, that is, the dispersion of questions regarding the

average. If the variance is equal to 0, it means that all the students have

answered the question in the same way; on the contrary, if it increases, it

indicates that more students think differently. Nevertheless, a detailed

analysis of the answers will only be done if the value is high, as it may

reveal that there are responses contrary to the mean value, which, in some key

questions (Appendix 4), may be relevant but not detected in the mean values of

the global class. However, a high value in other questions such as “The class

is tidy, so I'm comfortable”, may simply indicate that a class may have

different criteria for a topic.

Once the two checks have been made, both for the

individual and group responses, the data is used to obtain and evaluate the

classroom atmosphere. To obtain a value that represents the environment, each

question has four answers: always, usually, sometimes, and never where the most

positive is given 4 points and the most negative 0. The sum of all the

individual scores of each of the answers allows the researcher to obtain the

total value of the class to form a scale. In addition, the questions are grouped

into 5 variables; this will allow the researcher to see which are the

weaknesses in each of the classes analysed and

therefore should be improved. This process is repeated for each of the

classrooms, as it may be reliable for one sample of students but not reliable

for another.

Piloting the instrument

To conduct the investigation, principals and primary

school coordinators of the different schools were contacted via e-mail. These

professionals arranged a pre-face-to-face meeting with the researcher at the

school, so that they could check the questionnaire and talk about the day,

time, and courses where the implementation would take place. In this meeting, it was also discussed in which courses the

questionnaire would be administered through Google Forms using the

schools’ devices and in which courses the printed questionnaire would be used.

On the day the study was conducted at the school, the

researcher went from class to class explaining the instructions of the

questionnaire and solving questions to children who needed it, while the class

teacher, who had received instructions in advance, directed the application of

the questionnaire. It should be noted that the questionnaire was administered

in Catalan or English, depending on the school’s official language, but as

mentioned in the «creation of the instrument» section, if a student did not yet

speak the official language of the school, the child was allowed to complete

the questionnaire in his or her mother

tongue to ensure that all students understood what was being asked. In terms of

time, the students took an average of 15-20 minutes to complete all the

questions.

Participants

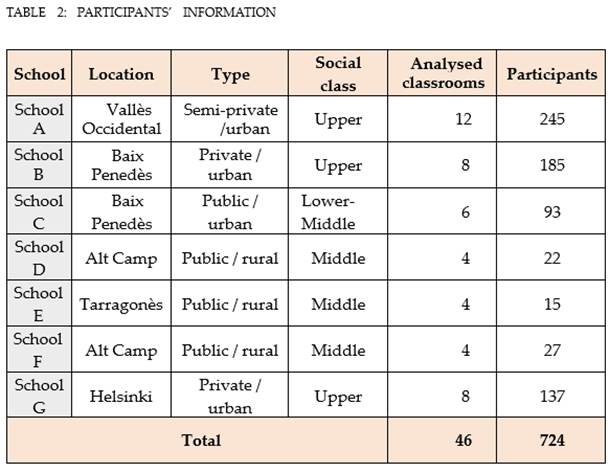

The study was carried out in 24 middle

cycle classrooms (8-10 years old) and 22 of the upper cycle (10-12 years old)

coming from private, semi-private, public, urban, and rural schools from

different areas of Catalonia, as shown in the table below. In addition, the

instrument has also been applied to a semi-private school in Helsinki to

evaluate the effectiveness of the tool in other contexts. All students in these

schools will have to answer all the questions individually, avoiding

interaction between classmates to ensure that everyone answers what they think

without being influenced. As can be seen in the table below, the names of the

schools have been replaced by the letters A to G in order to

maintain the anonymity of the schools participating in the study.

Results

The main result of this research is the questionnaire

explained in the «Methods» section. Therefore, this part will show the

validation results and examples on how to apply and analyse

the instrument information, to present in a practical way how the instrument

works.

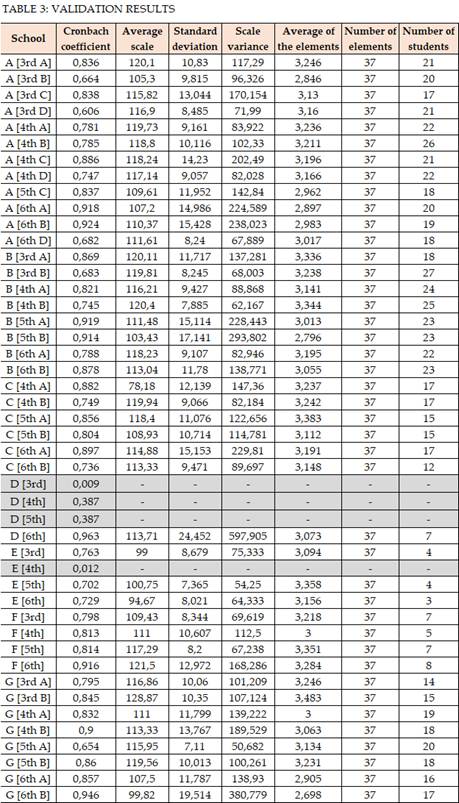

Before interpreting the validation

results, it is worth considering that the consistency and reliability of the

data had to be analysed through four checks. Firstly,

if the students answered all the questions, secondly, the correlation of the

repeated questions, which should be around 1, then the correlation of the

similar and opposite questions, and finally the Cronbach's alpha. The facts in

a sample are considered very reliable if the Cronbach alpha is above 0.7 and

unreliable if it is below 0.5. Therefore, all the classes that did not exceed

this value, and consequently are not considered reliable, have been marked in

red and the next step, which is to interpret the data, was not carried out.

Once the researcher was sure the

information is reliable, the interpretation of the data is carried out (table

3), where the following values are analysed: the

arithmetic mean of all the questions, the standard deviation and the variance,

which indicate how much the answers vary with respect to the mean, the value of

the key questions where low values should appear and, finally, the number of

students, since one student in a class of 25 students is equivalent to 4% while

one student in a class of 4 students represents 25% of the class. As the table

shows, the values obtained in 42 out of 46 classrooms are consistent, so the

tool is validated.

Before starting with the analysis of the results, it

is necessary to check the reliability of the data, as mentioned in the

«validation of the instrument» section. Once it has been verified that all the

data provides information, the researcher proceeds to represent the average

values of the class classified in the 5 variables through a graph to facilitate

understanding. Some samples from different schools have been analysed to show in a practical way how the tool works.

Discussion

The result of the study, which is the creation of a

new tool for assessing the climate in the classroom, shows that the first

objective has been achieved. The results of several authors who had already

studied and created previous questionnaires but with different objectives in

mind, were considered to implement this instrument. Therefore, these results

will be discussed in the light of the literature review below.

As stated by Perez, Ramos & Lopez (2009) in the

journal article, the following variables are essential to evaluate the

classroom environment: interest, satisfaction, relationship, and communication.

For this reason, the same dimensions have been included in this study, but

separating the questions related to teacher-student relationships and

student-student relationships. These two variables must be evaluated separately

because they reveal different information. One may be well appreciated by the

students, while the other may not, and to improve each of them different

measures should be applied. In terms of the questions, this study has also been

inspired by those of Perez, Ramos & Lopez (2009), but as mentioned in

previous sections, due to the year of research it does not cover all the

characteristics that surround the current classrooms such as new technologies

and disadvantages of this area, for example, cyberbullying. It also does not

include other key aspects such as physical education or bullying, so the

following authors have also been considered in the creation of the new tool.

As stated in the journal article by González, Touron and Tejedor (2012), when assessing the classroom

environment, one must also consider how students feel about the distribution of

the class, orderliness, and noise. For this reason, questions related to this

area have been included in the results of this new tool which has enriched the

results of this study.

Moreover, in the final product of this study,

questions have been added to detect bullying, since the study by Vásquez,

Zuluaga and Fernández (2012) ensures that bullying is a social reality which is

present in many of the classrooms affecting peer relationships.

Finally, the last instrument includes questions about

new technologies that affect students in almost all variables, which is why the

article by Mousavi, Mohammadi, Mojtahedzadeh, Shirazi

and Rashidi (2020) has been considered.

The tool for evaluating the classroom environment is a

questionnaire that translates the answers; always, sometimes, several times and

never into numbers; 1, 2, 3, 4, to be able to process them through a program

that draws statistics from the data obtained. The questionnaire gathers 37

questions to evaluate 5 variables; interest and motivation, satisfaction,

teacher-student relationship, peers’ relationship, and communication;

considering new technologies, student fear, bullying…

Before being analysed, a

series of checks are carried out to ensure that all the data are reliable and

finally the average of each variable is plotted on a graph. This tool has been

validated through the evaluation of 6 Catalan schools with different

characteristics and one in Helsinki to check the effectiveness of the

instrument in different contexts.

Returning to the objectives established in the

introduction, each of them has been fulfilled in this article. As objective A

“create and validate a new instrument to assess the classroom atmosphere so

that it adapts to the new characteristics that surround the students of the

second and third cycle in the current classrooms” indicates, in this study, a

tool that assesses classroom environment has been created and statistics were

run to validate it. This program has allowed the researcher to know that all the

results obtained and analysed in this academic paper

are coherent and, as a result, announces that no question should be discarded

from the tool. It should be noted that the data from four rural school

classrooms were not interpreted due to the low Cronbach's alpha value obtained.

In addition, considering objective B “analyse samples from a school to present in a practical way

how the instrument works”, six samples from different schools have been analysed, the results of each class have been represented

through a graph to make it easier to understand. In each class, the results of

each of the variables obtained are higher than the minimum acceptable,

therefore, it could be said that all the samples evaluated can have a good

classroom environment.

Finally, as the last objective indicates «validate and

check the effectiveness of the instrument in schools with different contexts,

such as private, semi-private, public and rural schools in Catalonia and one

Finnish school», to validate the instrument, 46 samples of schools with

different characteristics and contexts were analysed.

In this way, this study has represented a real sample of all the varieties of

schools in society, segregated by gender, mixed, private, semi-private, public,

rural, and international. For this reason, it could be said that diverse and

significant data were obtained for statistical validation.

In conclusion, it could be stated that the instrument

works well because it has identified the different strengths and weaknesses of

each classroom. It should be noted that a more detailed analysis of the less

valued variables allows us to know which of the questions lowers the average,

and as a result, the teacher could apply corrective measures to continuously

improve all the variables. To see the evolution, this tool should be

implemented from time to time to ensure that there is a good environment in a classroom.

It is noteworthy that this article has gone beyond the objectives set out in

the introduction because, as observed in the analysis of the four schools, the

high values of variance of the key questions (Appendix 4) could detect cases of

discomfort, insecurity or even bullying. To check which student is or to detect

if it coincides that the same student evaluates negatively more than a

dangerous question, an individual evaluation of each questionnaire is carried

out. However, this could be considered as a future extension of this work

because it should be confirmed again by visiting the school to see if it has

been a specific issue that affected the student in deciding the answer, or even

the tool can be re-executed if necessary to see if the student answers the

same.

References

Almenara, J. C. (2007). Tecnología educativa [Educational technology]. Mc Graw

Hill.

Arón, A. M., & Milicic, N. (1999). Clima

social escolar y desarrollo personal. Un programa de mejoramiento [School social climate and personal development. An improvement programme]. Andrés Bello.

Artavia Granados, J. M. (2005). Interacciones personales entre docentes y estudiantes en el proceso

de enseñanza y aprendizaje

[Personal interactions between teachers and students in the teaching/learning

process]. Revista

Electrónica Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 5(2), 1-19. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/447/44750208.pdf

Brandt, P. A., & Weinert, C. (1981). The PRQ: a social support measure [PRQ: una medida

de apoyo social]. Nursing Research, 30(5), 277-280. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198109000-00007

Baños, R., Ortiz-Camacho, M. M., Baena-Extremera, A., & Tristán- Rodríguez, J. L.

(2017). Satisfacción, motivación

y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de Secundaria

y Bachillerato: antecedentes, diseño, metodología y propuesta de análisis

para un trabajo de investigación [Satisfaction, motivation, and academic performance in students of secondary and baccalaureate: background, design, methodology and proposal of analysis

for a research paper]. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 10(20),

40-50. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5900741

Barreda, M. (2012). El docente como gestor del clima del aula.

Factores a tener en cuenta [The

teacher as a manager of classroom climate;

Master’s tesis, Universidad de Cantabria].

Repositorio UCrea. https://repositorio.unican.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10902/1627/Barreda%20G%C3%B3mez,%20Mar%C3%ADa%20Soledad.pdf?sequence=1

Biggs, J. (2005). Calidad del aprendizaje universitario [Quality

of university learning]. Narcea.

Biscarri Gassió, J. (2000). Condicionantes

contextuales de las atribuciones de los profesores respecto del rendimiento de

sus alumnos [Contextual determinants of teachers‘ attributions of

their students’

performance]. Revista de Educación, 323,

475-492. https://www.educacionfpydeportes.gob.es/dam/jcr:7d9f2015-7750-4adb-a7c0-a41405e91810/re3232208918-pdf.pdf

Camargo Uribe, Á. C., & Hiederich

Martínez, C. H. (2007). El estilo de comunicación y su presencia en el aula de

clase [Communication style

and its presence in the classroom]. Folios,

(26), 3-12. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3459/345941356001.pdf

Cela Sangrá, J.,

& Palou Ollé, J. (1997). El Espacio [Space]. Cuadernos de Pedagogía,

(254), 68-70. https://www.cuadernosdepedagogia.com/

Cuadrado Reyes, B. (2009, june). El profesorado como líder grupal.

Innovación y Experiencias educativas

(19). Centro Sindical Independiente y de Funcionarios.

https://www.csif.es/es/articulo/andalucia/educacion/39102

Dugarte, A., & Guanipa, L. (2009). Las TIC, medios didácticos

en Educación Superior [The

ICT teaching strategies in Higher Education]. Revista Educación, 19(34), 106-125. http://servicio.bc.uc.edu.ve/educacion/revista/n34/art5.pdf

Estévez, E., Musitu Ochoa, G., & Herrero Olaizola, J.

(2005) El rol de la comunicación familiar y del ajuste escolar en la salud

mental del adolescente [The Role of

Family Communication and School Adjustment in Adolescent Mental Health]. Salud

Mental, 28(4), 81. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/582/58242809.pdf

Figueroa, M. L. (2012). Principales modelos de liderazgo: su significación en el ámbito

universitario [Main leadership

models: its importance in university field]. Revista de Humanidades Médicas,

12(3), 515-530. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262665708_Principales_modelos_de_liderazgo_su_significacion_en_el_ambito_universitario

Frías-Navarro, D. (2021). Apuntes de consistencia interna de las puntuaciones de un instrumento de

medida [Notes on the internal consistency

of the scores of a measuring instrument; Brochure]. Universidad de Valencia, Spain. https://www.uv.es/friasnav/AlfaCronbach.pdf

Gairín Sallán, J. (1995). El reto de la

organización de los espacios [The challenge

of space organisation]. Aula de Innovación Educativa, (39). https://ddd.uab.cat/record/183074

Gámiz, V. (2009). Entornos virtuales para la formación

práctica de estudiantes de educación:

implementación, experimentación

y evaluación de la plataforma aula- web [Virtual

environments for the practical training of education students:

implementation, experimentation

and evaluation of the Web Classroom platform; Doctoral dissertation,

Universidad de Granada]. Digibug. https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/2727

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS

for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th

ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Goleman, D. (1999, january).

Qué define a un líder [What makes a leader]. Revista Dinero. https://www.bancoldex.com/sites/default/files/documentos/6485_Modulo_1_-ARTICULO_que-define-a-un-lider-goleman.pdf

González, A., Conde, Á., Díaz, P., García, M., & Ricoy, C. (2018). Instructors’ teaching

styles: Relation with competences, self-efficacy, and commitment in pre-service

teachers. Higher Education, 75(4), 625-642. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318162260_Instructors'_teaching_styles_relation_with_competences_self-efficacy_and_commitment_in_pre-service_teachers

González, E. L., Touron, J. T., &

Tejedor, F. J. T. (2012). Diseño de un micro-instrumento

para medir el clima de aprendizaje en cuestionarios de contexto [Design of a micro-instrument for the measurement of learningclimate useful to develop

context questionnaires]. Bordón. Revista

de pedagogía, 64(2), 111-126. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/22000

López-González, L., & Oriol, X. (2016). La relación

entre competencia emocional, clima de aula y rendimiento académico

en estudiantes de secundaria [Design of a micro-instrument for the measurement

of learningclimate useful to develop

context questionnaires]. Cultura y Educación, 28(1), 130-156. https://researchers.unab.cl/es/publications/la-relaci%C3%B3n-entre-competencia-emocional-clima-de-aula-y-rendimien

López Hernáez,

L., & Sabater Fernández, C. (2019). Acoso Escolar: Definición,

características, causas-consecuencias, familias como agente clave y prevención-intervención

ecológica [Bullying: Definition, characteristics, causes and consequences, families as key agents and

ecological prevention-intervention].

Ediciones Pirámide.

Madrigal Torres, B. (2004). Liderazgo: Enseñanza

y Aprendizaje [Leadership:

Teaching and Learning].

McGraw Hill Interamericana.

Maldonado Díaz, C. A. (2016). Clima de Aula Escolar y Estilos

de Enseñanza: Asociación y Representaciones Expresadas por Profesores de Educación Básica en la Comuna de Quilpué

[School Classroom Climate and Teaching

Styles: Association and Representations Expressed by Basic Education Teachers in the Municipality of Quilpué ; Master’s thesis, Universidad de Chile]. Repositorio de la U. de Chile. https://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/145260/Clima%20de%20Aula%20y%20Estilos%20de%20Ense%c3%b1anza.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Manzano, D., & Valero-Valenzuela, A.

(2019). El modelo de responsabilidad personal y

social (MRPS) en las diferentes materias

de la educación primaria y su repercusión en la responsabilidad, autonomía, motivación, autoconcepto y clima

social [The teaching

personal and social responsibility

model (TPSR) in the different

subjects of primary education and its

impact on responsibility, autonomy, motivation, self-concept and social climate.]. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 11(3). https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/JSHR/article/view/80924

Manzano-Sánchez, D. (2021). Diferencias

entre aspectos psicológicos en Educación

Primaria y Educación Secundaria. Motivación,

Necesidades psicológicas básicas,

Responsabilidad, Clima de aula, Conductas antisociales y Violencia [Differences between psychological aspects in Primary Education and Secondary Education. Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Responsibility, Classroom

Climate, Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors and Violence]. Espiral: Cuadernos del

Profesorado, 14(28), 9-18. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7783033

Marqués, P. (2010). Impacto de las TIC en educación:

Funciones y limitaciones [The Impact

of ICT in Education: Roles

and Limitations]. Pangea.

Martín Díaz, V. (2009). Las TIC y el desarrollo de las

competencias básicas. Una propuesta

para Educación Primaria [ICT

and the development of basic skills. A proposal for Primary Education]. Eduforma.

Moreno Madrigal, C., Díaz

Mujica, A., Cuevas Tamarín, C., Nova, C., & Bravo

Carrasco, I. (2011). Clima social escolar en el aula y vínculo profesor-alumno: alcances, herramientas de evaluación, y programas de intervención

[Social School Climate in the Classroom and the Link Professor-Student: Scopes,

Evaluation Tools, and Intervention Programs]. Revista

Electrónica de Psicología

Iztacala, 14(3), 70-84. https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/repi/article/view/27647

Moreno Ruiz, D., Estévez López, E., Murgui Pérez, S, & Musitu

Ochoa, G. (2009). Relación entre el clima familiar y el clima escolar: El rol de la

empatía, la actitud hacia la autoridad y la conducta violenta en la

adolescencia [Relationship between

family climate and school climate: The role of empathy,

attitudes towards authority and violent behaviour in adolescence.]. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 9(1) 123-136. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/560/56012876010.pdf

Mousavi, A., Mohammadi, A., Mojtahedzadeh, R., Shirazi, M., & Rashidi, H. (2020).

E- Learning Educational Atmosphere Measure (EEAM): A New Instrument for

Assessing E-Students' Perception of Educational Environment. Research in

Learning Technology, 28. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v28.2308

Munne, M. (2015). Los 10 principios de la

cultura de mediación [The 10 principles

of mediation culture].

Graó.

Oñate Cantero, A., & Piñuel y Zabala, I. (2007). Informe

Cisneros X: Acoso y violencia escolar en España [Bullying and school violence in Spain]. IIEDDI. https://bienestaryproteccioninfantil.es/informe-cisneros-x-acoso-y-violencia-escolar-en-espana/

Pérez Carbonell, M. A., Ramos Santana, G., & López González,

E. (2009). Diseño y análisis de una escala para la valoración de la variable

clima social aula en alumnos de Educación Primaria y Secundaria [Design and analysis of an evaluation

scale of the climate classroom

social variable for primary

and secondary education pupils]. Revista de Educación, (350), 221-252. https://produccioncientifica.ucm.es/documentos/5eb09e522999527641137c6a

Perrenoud, P. (2005). Diez nuevas competencias para enseñar [Ten new teaching skills]. Graó.

Quintana, J. M. (1980). Pedagogía

social [Social Pedagogy]. Dykinson.

Rojas Bravo, J. (2013). Clima escolar y tipología

docente: la violencia escolar en las prácticas

educativas [School climate

and teacher typology: school violence in educational practices]. Cuadernos

de Investigación Educativa, 4(19), 87-104. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4436/443643892006.pdf

Rovira-Mañé, M. (2022, 22 de abril). Audio:

Classroom environment questionnaire [Video]. YouTube.

https://youtu.be/FDDTWmHSf4o

Vásquez, N. S. M., Zuluaga, N. C., &

Fernández, D. Y. B. (2012). Validación de un cuestionario breve para detectar intimidación

escolar (Validation of a

Short Questionnaire to detect School Bullying). CES Psicología, 5(2), 70-78.

https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4235/423539471006.pdf

Vieira, H. (2007). Comunicación en el aula [Communication in the classroom]. Narcea.

Unesco. (2014). Teaching and Learning:

Achieving quality for all. https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/teaching-and-learning-achieving-quality-for-all-gmr-2013-2014-en.pdf

Villanueva, R. (2016). Clima de aula en secundaria: un análisis

de las interacciones entre docentes y estudiantes [Classroom

climate in secondary school: an analysis

of teacher-student interactions; Tesis de Licenciatura no publicada]. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Wilkinson, L., & APA Task Force on

Statistical Inference (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals:

Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54, 594-604. https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-54-8-594.pdf

APÉNDICES

Appendix 1-A: Questions grouped in the variables studied. Prior to expert

validation

|

Variable |

QUESTIONS |

|

Interest and motivation |

1. Teachers are personally interested in

each of us when we have doubts or any problems, both inside and outside the

class hours. |

|

6. Teachers show respect for our

feelings. |

|

|

11. Teachers use different methods to

encourage group activities, motivate us and get involved in our learning

process |

|

|

16. Teachers send homework short, fun,

varied and meaningful, which helps to increase my motivation to learn. |

|

|

21. Teachers send us repetitive assignments and they are boring. |

|

|

26. It is easy for me to study and do my

homework and online activities suggested by the teacher. |

|

|

31. It is noticeable that the teachers

do not prepare the classes because it does not give

them time to finish them and that is why they make us finish it at home. 36. The teacher explains the theory to us very

well and makes sure that we understand it, in the

negative case he explains it to us as many times as necessary. |

|

|

36. The teacher explains the theory to

us very well and makes sure that we understand it, in the negative case he explain it to us many times as necessary. |

|

|

Satisfaction |

2. Students are happy with the class

group. |

|

7. The students are proud of the layout,

order, learning materials of the class and as a

result allow us to work comfortably in the classroom. |

|

|

12. My classmates don't respect the class, there's always clutter in the classroom and that

makes me uncomfortable in this space. |

|

|

17. I think my class is a nice place (I

like being in my class). |

|

|

22. The teachers know how to answer all

the doubts of the syllabus without hesitation, it is

noticeable that they master what they tell us and

they transmit knowledge to us. |

|

|

27. Teachers master new technologies

(digital competence) and use them correctly for activities inside and outside

the classroom. |

|

|

32. There are class interruptions and/or

classroom noises, which prevent me from following them. |

|

|

Teacher-student relationship |

3. The relationship between teachers and

students is cordial. |

|

8. The relationship between us and the

teachers is pleasant. |

|

|

13. My teachers appreciate me |

|

|

18. Teachers don't listen to me when I have to tell them something |

|

|

23. There is a lot of pressure from

teachers as they demand more of us than we can do and as a result we get

stressed out. |

|

|

28. The relationship with the teacher is

very distant, and therefore it makes me respectful to ask all the doubts I have. |

|

|

Student-student relationship |

4. In this class, students have a good

relationship with each other. |

|

9. The students collaborate very well

with each other. |

|

|

14. My classmates don't let me

participate and tell others not to be with me or not to talk to me and

consequently make me feel inferior (exclude me). |

|

|

19. My classmates don't respect my stuff

(they break it, they hide it from me...) |

|

|

24. My classmates physically or

psychologically assault me (beat me or insult me) |

|

|

29. The students appreciate me and are

my friends. |

|

|

34. I feel discriminated against by my

peers for some reason (race, religion, gender, social status...) 39. When I

come to school I feel fear or anguish over my

relationship with my classmates. |

|

|

39. When I come to school, I feel fear

or anguish over my relationship with my classmates. |

|

|

44. My classmates send me offensive

messages or drawings on the internet and/or mobile. |

|

|

Communication |

5. In this class, the students have very

good communication with the teachers. |

|

10. In this class, students have very

good communication with each other. |

|

|

15. Teachers have good communication

with each other, and this benefits us because we do not accumulate exams and

homework on the same day but are well distributed. |

|

|

20. I get nervous or anxious when I

attend class. |

|

|

25. During online classes, my ability to

interact with others has increased because I feel comfortable and safe in

asking my questions in online classes. |

|

|

30. My parents' relationship with the

school and the teachers is good. |

|

|

35. My parents are angry with the

school. |

Appendix 1-B:

Questions grouped in the variables studied. After expert validation

|

Variable |

QUESTIONS |

|

Interest and motivation |

1. Teachers pay attention to me when I

have a problem or want to report that I have seen a conflict between

classmates, both inside and outside of class hours. |

|

6. Teachers care about how I am. |

|

|

11. I like the different activities we

do in class. |

|

|

16. I like the homework that teachers

send us. |

|

|

21. Our homework is boring. |

|

|

26. It is easy for me to hand in my

homework online. |

|

|

30. We have time to finish the

activities in class. |

|

|

34. I understand what the teachers explain me in class. |

|

|

Satisfaction |

2. I am happy with my classmates. |

|

7. I like the different spaces in the

class, because they allow me to work at ease. |

|

|

12. The class is tidy, so I'm

comfortable. |

|

|

17. I think my class is a nice place and

I have everything I need. |

|

|

22. The teachers answer

all my questions. |

|

|

27. Teachers know how to use new

technologies to do activities. |

|

|

31. I find it hard to concentrate with the noises of my classmates, of class or out of

class. |

|

|

Teacher-student relationship |

3. I am comfortable with the teachers. |

|

8. Teachers tell us what we do and how

we feel. |

|

|

13. Teachers listen to me when I have to tell them something. |

|

|

18. Teachers demand more of me than I can do. |

|

|

23. I'm ashamed to ask teachers

questions. |

|

|

37. I dare tell teachers if I see a

classmate hitting, insulting, or breaking another classmate's material. |

|

|

Student-student relationship |

4. All our colleagues are very friendly

with each other. |

|

9. We help each other among

classmates. |

|

|

14. My classmates want to play with me. |

|

|

19. My classmates break or hide my

classroom material. |

|

|

24. My classmates hit me or insult me. |

|

|

28. I have fun with my classmates. |

|

|

32. There are conflicts between peers. |

|

|

35. I feel safe coming to the school. |

|

|

36. Classmates write me

bad things on paper, on the table... |

|

|

Communication |

5. I can communicate well with teachers. |

|

10. I can communicate well with

classmates. |

|

|

15. Teachers talk to each other in order

not to have a lot of homework or exams in the same week. |

|

|

20. I get nervous when I participate in

class. |

|

|

25. I enjoy talking to my classmates in

online classes. |

|

|

29. My parents are happy with the school

and the teachers. |

|

|

33. My parents are angry with the school

and/or teachers. |

Autores

Marta

Rovira-Mañé

Es licenciada en Educación Infantil y

Primaria con mención en inglés y pertenece al cuerpo docente del Ministerio de

Educación desde mayo de 2024. Ha participado activamente en proyectos de

investigación que abordan la inclusión educativa y la diversidad cultural en el

aula, habiendo ganado el concurso ODS de la Agenda 2030 impulsado por la Universitat Internacional de Catalunya en 2022.

Jaume

Camps Bansell

Es licenciado en Historia y

doctor en Humanidades, este último por la UIC (Universitat

Internacional de Catalunya). Es profesor de Teorías Educativas y Sociología de

la Educación en la Universitat Internacional de

Catalunya. Sus intereses en investigación se han centrado en las cuestiones de

género en educación, así como en las relaciones entre los agentes escolares;

sobre esos aspectos ha publicado libros y en revistas científicas. Ha publicado

diversos artículos científicos y participado en numerosos congresos.

Esta

obra se publica bajo licencia:

Creative Commons

BY-NC-SA 4.0 Internacional

(Reconocimiento – No comercial – Compartir igual)

ISSN-L 2224 7408

eISSN 3078 4913